CERF Blog

Previously published in the 2018 Quarter 4 US Economic Forecast – December 19, 2019

For years, we have been telling anyone who will listen that extraordinary policy experimentation undertaken by the Federal Reserve during the darkest days of the financial crisis remains a major impediment to robust economic growth for the nation.

Facing economic meltdown in 2008, the Federal Reserve did two extraordinary things.

In October of that year, facing fears of a massive deflation, the Central Bank started to pay interest on reserves (IOR) for the first time in its history. IOR simply means that the Federal Reserve pays interest on all funds that commercial banks deposit at the Central Bank. The initial IOR rate was just 0.25 percent. Amazingly, paying one quarter of a percent had a transformational effect on commercial banking in the United States.

Normally, commercial banks lend out the vast majority of money deposited by savers. This lending provides critical financial intermediation, making credit available to a giant class of economic actors who then engage in personal consumption, household formation and small business creation. In this way, commercial bank lending is a central driver of economic growth in the United States.

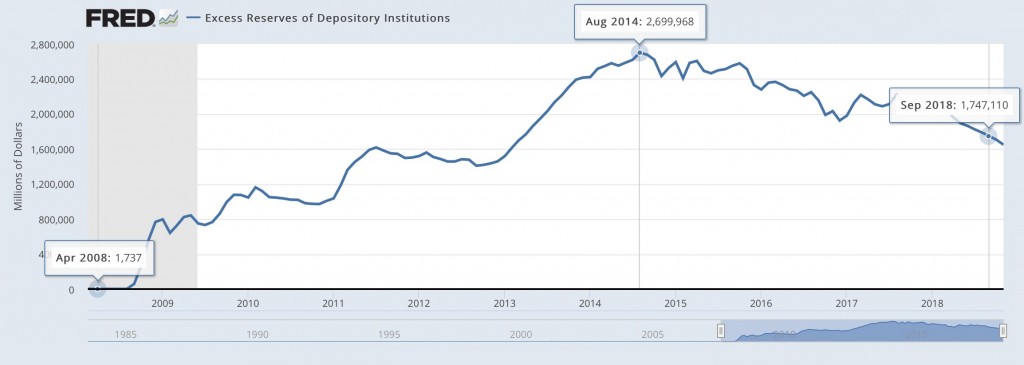

As of April 2008, excess reserves, the amount that commercial banks store at the Central Bank in excess of their reserve requirement, totaled just 1.7 billion dollars for all U.S. banks. That is, banks preferred to lend customers’ deposits in order to create a financial return for the bank and thus kept excess reserves to a minimum. By August 2014, with the Federal Reserve now paying interest to commercial banks, excess reserves swelled to over 2.7 trillion dollars. That is more than a thousand-fold increase in the amount of money parked at the Central Bank. Suddenly, banks preferred to store customers’ deposits at the Central Bank where it could earn a risk-free return rather than lending those funds. Critically, 2.7 trillion dollars was retired from economic activity, no longer providing financial intermediation in the U.S. economy.

This is one of the primary drivers of anemic economic growth in the United States since the Great Recession. From the end of the Great Recession until the beginning of 2018, the U.S. economy averaged just 1.9 percent growth, a level well below the post-World War II average growth rate of 3.5 percent and even farther below the growth rates experienced during previous economic recoveries.

As time passed and the country moved farther and farther from the financial crisis, we earnestly hoped that the Federal Reserve would gradually unwind the policy of IOR. Instead, what they have done is repeatedly increase the interest paid to commercial banks. In fact, each of the nine increases in the Federal Reserve’s short term interest rate target since the recession has been accompanied by an increase in the interest rate paid on reserves. Currently, a U.S. commercial bank can earn 2.40 percent by parking money, risk free, at the Central Bank.

There are still more than 1.6 trillion dollars sidelined in Central Bank coffers, nearly 1,000 times the pre-IOR level.

This begs the question, why isn’t the Federal Reserve returning to normal monetary policy? Why isn’t the Fed reversing this extraordinary policy intervention, now that the economy is gaining strength?

The reason that the Federal Reserve must continue to increase IOR despite the negative effect it has on financial intermediation and economic growth is because of the second extraordinary policy intervention that the Fed undertook during the financial crisis – the dramatic expansion of its balance sheet.

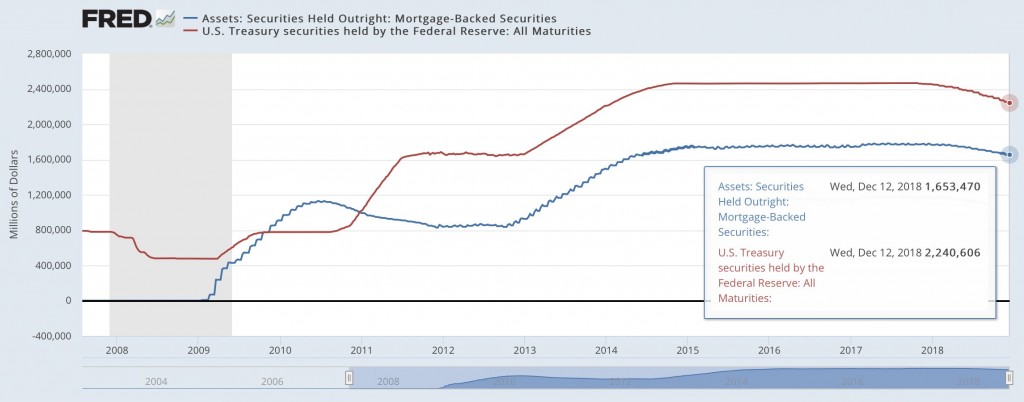

Beginning in January 2009, worried about the solvency of major U.S. banks, the Federal Reserve began purchasing toxic assets, in particular mortgage backed securities (MBSs), from banks. The goal was to keep the banks solvent by cleaning up their balance sheets. The purchase of large amounts of MBSs marked the beginning of an unprecedented expansion of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. In all, nearly 1.8 trillion dollars in MBSs were purchased by the Fed.

Expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet accelerated beginning late in 2010 when the Federal Reserve engaged in the purchase of large amounts of U.S. Treasury securities. This quantitative easing was designed to fend off a double-dip recession by increasing the money supply. A second round of QE began in early 2013. By the end of 2014, the amount of U.S. Treasuries held by the Federal Reserve totaled more than 2.4 trillion dollars. Between treasuries and MBSs, the Fed’s balance sheet swelled to more than 4 trillion dollars in assets, a level never before imagined.

We believe that the unprecedented expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet is the reason that the Federal Reserve must continue to pay (and must pay an increasingly high rate of) interest on reserves.

Anyone who has taken an undergraduate course in Macroeconomics will recall that the way the Federal Reserve has historically achieved its short term interest rate target was by buying and selling treasuries, altering the supply and demand for these government financial instruments, in order to move the short term market interest rate toward its target. These open market operations, along with manipulation of the level of reserves, allowed the Fed to move the market. In this new era of extraordinary monetary policy, there is only one short term interest rate that matters – IOR. Small changes in the supply and demand for Treasuries can never hope to influence short term market rates the way that IOR does.

Plainly, the Federal Reserve has broken the machine. Now they increase the short term market interest rate by increasing the interest rate paid to commercial banks. Every increase in the short term interest rate target is necessarily accompanied by an increase in IOR, a move which will surely influence short term market interest rates but which also threatens to reduce financial intermediation in the economy.

For further evidence that the machine is broken, consider the yield curve. During the first week of December, the yield on the 5-Year Treasury actually fell below the yield on the 2-Year Treasury. The risk and liquidity premia usually required to induce investors to hold longer term instruments appeared to vanish. In normal times, an inversion of this kind signals economic weakness and can even portend recession, as the usual cause of an inversion is a rush on the part of investors to lock in yield in anticipation of falling interest rates. The last time that the 2- and 5-year yields inverted was 2007. The latest inversion, on December 3, was widely dismissed as being meaningless. You see, market interest rates are unhinged from economic fundamentals. Everyone understands that the yield curve no longer contains the information that it once did.

What all of this means is that we will not see a return to normal monetary policy until the Fed unwinds the 3.9 trillion dollars of assets still on the Fed’s balance sheet. The Federal Reserve currently plans to reduce that balance sheet at a rate of only 50 billion dollars per month. This means that, even if the economy continues to grow for another 6 years, the Federal Reserve will still not have achieved normalization until at least 2024.

And the next recession, which is guaranteed to arrive sometime in the next 6 years, will surely force the Federal Reserve to pause or even reverse its path of policy normalization.

Normalization of monetary policy is long overdue. As we have argued previously, the Federal Reserve should have begun a sustained increase in interest rates, a significant reduction of its balance sheet and an end to interest on reserves beginning in 2012. Instead, normalization has proceeded at an entirely anemic rate.

To our horror, there are now widespread calls for the Fed to pause its path of policy normalization. Recent policy pronouncements, in particular communication of the Fed’s plan to increase short term interest rates, have been met by large stock market declines. As of this writing on December 19, the Dow Jones Industrial Average has declined more than 850 points in less than one hour following the Fed’s announcement of the most recent rate increase.

Stock market turbulence is being held out as evidence that the Fed should now delay interest rate hikes.

This is a seriously flawed argument. Bad monetary policy is a significant cause of inflated equity market prices. The Federal Reserve held the short term interest rate target at 0 percent from December 2008 until December 2015. Extraordinarily low interest rates drove investors into equity markets, in search of yield. This was an explicit goal of monetary policy during these years. It was entirely predictable that equity markets would respond to the inevitable increase in interest rates. Rather than a reason to pause, stock market declines are a necessary element of monetary policy normalization.

Normalization is long overdue. Today’s Fed Funds rate, with a target range of 2.25 to 2.5 percent, is still well below the long term average of more than 5 percent.

In our view, the worst thing that the Federal Reserve can do now is blink. Yielding to short term concerns and failing to move decisively in the direction of policy normalization will only make normalization harder (and perhaps even impossible) in the future. Without significant normalization, the Fed is likely to find that its hands are tied once the next economic downturn arrives.

Just imagine entering a recession when the Fed Funds target rate is already at a historically low level and the Fed’s Balance sheet is still near an all-time high. The only policy tool that the Fed will have at its disposal is a reduction in the interest rate paid on reserves. Unfortunately, since IOR is untested and poorly understood, no one knows what effect a reduction in IOR will have on an economy already undergoing contraction. Is a significant reduction in IOR an expansionary policy or a deflationary one?

We hope that the Federal Reserve doesn’t wait until the next Recession to find out.